Justin Barker, the 'Bear Boy' still fighting for zoo animals

PROFILE: Claire Hamlett spoke to ‘bear boy’ Justin Barker about his work campaigning against zoos following a profound realisation at just 13 years old. Part of our series on zoos and the release of our latest Surge video Why SHOULDN'T we support zoos and their conservation work?

Most kids who visit zoos on a family day out will get a momentary thrill from seeing a big animal like a lion or elephant or bear up close, get ice cream, maybe bug their parents to buy them something in the gift shop on their way out, then go home and get on with their lives.

Not Justin Barker. At 13 years old, Barker came across Ursula and Brutus, two black bears kept at a local zoo in Sacramento, California. Their enclosure was a small barren cage that flooded frequently due to its proximity to a creek and they were being fed food not meant for their species. Seeing how the bears were suffering, Barker knew he had to help them.

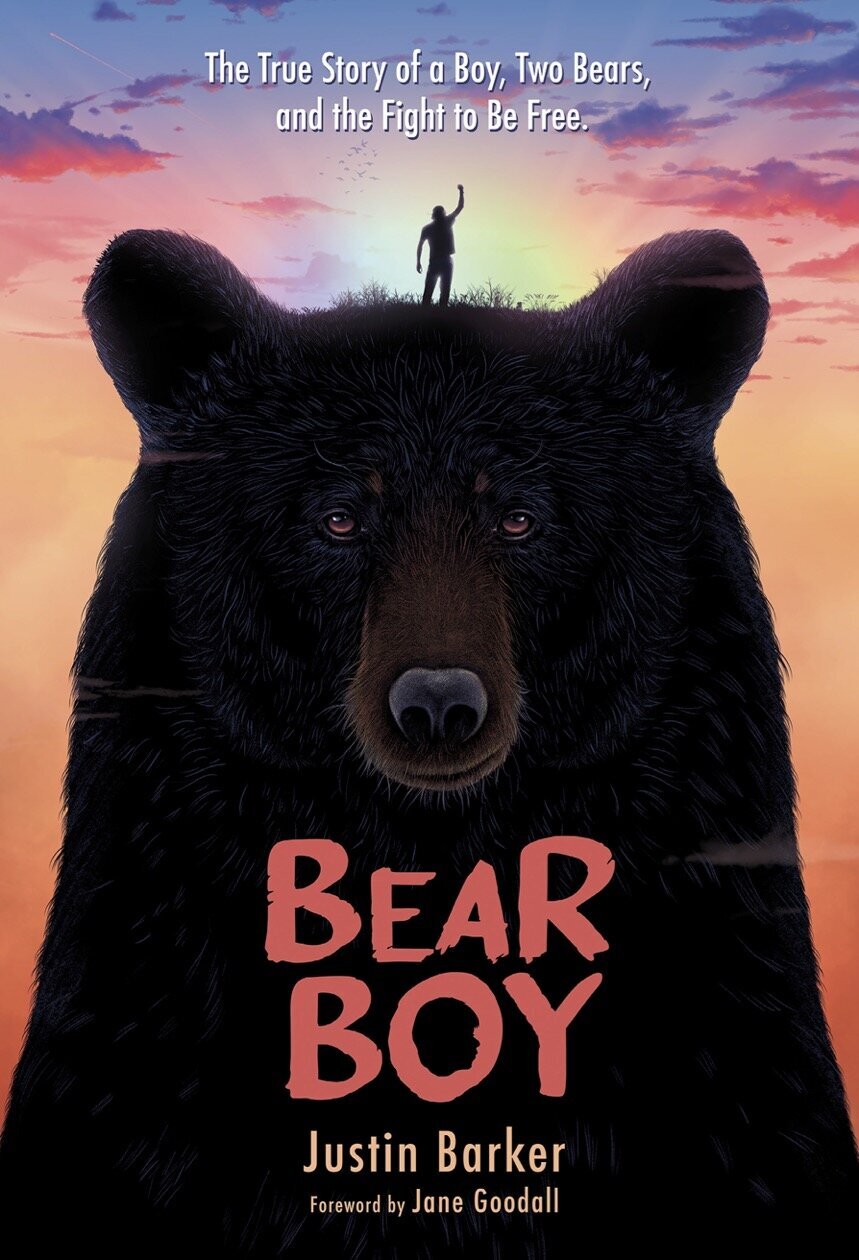

He recounts his mission to raise both awareness of the bears’ plight and the quarter of a million dollars needed to build them a new, more appropriate enclosure at another zoo in his memoir Bear Boy: The True Story of a Boy, Two Bears, and the Fight to Be Free, published in June this year. As it was the book Kids Can Save the Animals: 101 Easy Things to Do that first set Barker on his path to being an advocate for animals, creating “a massive change” in his life, he wrote Bear Boy “with the hopes that another young’un like me might find this book and get inspired to take action.”

More than 20 years have passed since Barker rescued Ursula and Brutus, but zoos are still failing animals and he is still holding them to account for it. Or trying to. “I've been in this very, very long, slow, arduous fight with the San Francisco zoo,” he says. Since Tanya Petersen, a former lawyer, took over as the zoo’s director in 2008, several incidents have occurred that have set alarm bells ringing in Barker’s head.

In 2014, a baby Western lowland gorilla was crushed to death by an automatic door in the gorilla enclosure. The zoo was accused of ignoring safety issues with that very door after another gorilla sustained a hand injury from it two years earlier. In 2015, Petersen defied the zoo’s accrediting body, the Association of Zoos and Aquariums (AZA), who wanted three chimpanzees moved to a different facility due to concerns that their accommodation at San Francisco zoo was not good enough.

“In an effort to better understand what's happening there … I have requested tons of documents” under California’s Freedom of Information Act, says Barker. “And [the zoo has] essentially broken the law by refusing to hand over any of the documents.” These include information on the number and types of animals at the zoo, a list of those being given pharmaceutical drugs - a common practice to combat the stress animals feel from living in captivity, as explained in Surge’s new video - and reports on any animal deaths that have occurred, as well as internal correspondence on such issues.

This kind of activism is hugely important for animals, as it can uncover information that will interest journalists, potentially affecting real change for those held in captivity. While Barker seems like a specialist zoo sleuth, he stresses that anyone who is concerned for zoo animals can do what he does. “I really encourage people just to focus on their local zoo,” he says. “If every single zoo in the world had an activist who was digging [into them], there'd be some really important accountability that a lot of zoos don't have right now.” The best way to get started, he says, is to understand “the laws in your city” and “what the management looks like at your local zoo.”

Never miss an article

Stay up-to-date with the weekly Surge newsletter to never miss an article, media production or investigation. We respect your privacy.

Though there has been some good media coverage of welfare problems at zoos over the years, Barker thinks too many zoo-related news stories gloss over the systemic problems that exist within the industry. Newspapers report excitedly on the births of baby animals or a zoo’s acquisition of new animals without interrogating what purpose those births or acquisitions are serving and whether they’re in the best interests of the individual animals or their species as a whole. “They want to keep breeding babies because they know that babies bring in the media and bring more people,” says Barker.

During the initial lockdowns of 2020, many outlets reported that zoo and aquarium animals were feeling lonely in the absence of human visitors. An aquarium in Japan even asked people to Facetime its eels to stop them from forgetting about humans. But a study into the behaviour of meerkats and penguins in several zoos during and after lockdown found that penguins didn’t seem to care whether there were visitors or not, while changes to the meerkats’ behaviour were too mixed to determine whether the return of visitors was more positive or more stressful for them. This indicates how the media is drawn to animal stories that have popular appeal, helping to entrench the idea that zoos are good for animals.

Visitors may not simply be able to rely on a zoo having official accreditation to feel confident that the animals are properly cared for or that their captivity is genuinely helping to conserve a species. In the US, being accredited by AZA “differentiates you from the roadside zoos,” says Barker. It shows that an AZA zoo has “some standards that a roadside zoo doesn't have.” But in his view the standards “are minimal.” Being an AZA zoo also means “you are kind of forced into doing what the organisation's vision is, and that's just perpetuating the same business model that has always existed.”

Though Barker believes most zoos as they currently function are not fit for purpose, he also believes that “if zoos were to radically shift their approach, they might have a place in our society.” They would need to become less of a commercial business and instead “focus on being sanctuaries for animals that need forever homes, and participating in actual in situ conservation.”

Claire Hamlett is a freelance journalist, writer and regular contributor at Surge. Based in Oxford, UK, Claire tells stories that challenge systemic exploitation of and disregard for animals and the environment and that point to a better way of doing things.

Your support makes a huge difference to us. Supporting Surge with a monthly or one-off donation enables us to continue our work to end all animal oppression.

LATEST ARTICLES